LANDLORD & TENANT

Things that you need to know before signing a Tenancy Agreement or a Lease

I. Things that you need to know before signing a Tenancy Agreement or a Lease

As an overview, a Tenancy Agreement is a binding legal document which has important implications on the committed rights and obligations on the part of both landlord and tenant. The terms of a Tenancy Agreement must be carefully considered before signing.

Contrary to the common belief of many lay parties, the potential consequences of breaching a Tenancy Agreement by a tenant may not be only limited to the ‘loss’ in the amount of the deposit paid to a landlord.

The same also applies to a landlord where he may become liable or responsible to third parties for any breaches committed by the tenant.

The contents of a Tenancy Agreement will normally include the period/length of the tenancy, rent, payment period, deposit, use (e.g. residence, office, or factory etc.), renewal terms, termination terms and other usual terms that will be described in the other parts of this topic.

Depending on the period of the tenancy and the capacities of the parties entering into the agreement (whether a party to an agreement is an individual or a limited company, etc.), different formalities for execution may be required.

While the terms "Tenancy Agreement" and "Lease" are often casually used as if they are synonyms in modern times and that both are generally binding, effective and enforceable in Court, there may still be some technical differences between them in their legal meaning.

Episode 1: Regulations on Tenancies of Subdivided Units

Episode 1: Regulations on Tenancies of Subdivided Units

In this episode, we will explain the Hong Kong government's amendments to the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance in 2021 for subdivided units for residential use, and how these new amendments protect tenants of subdivided units.

We will explain what a "regulated tenancy" is and whether tenants who have newly entered into tenancy agreements are already protected under the tenancy control.

The video will explain the key points of the tenancy control of subdivided units, including security of tenure, rent regulation, prohibition of excessive charging of utility bills, etc.

In addition, the video will also discuss the rights of existing tenants under the new amendments.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

After signing a Tenancy Agreement (or a Lease), how should the parties handle the document?

II. After signing a Tenancy Agreement (or a Lease), how should the parties handle the document?

A tenancy document is usually executed in counterparts, both of which are forwarded to the Stamp Office of the Inland Revenue Department for stamping within 30 days after the date of execution.

If the tenancy document is a Lease, then it should also be registered at the Land Registry within 30 days of the date of execution, otherwise it will lose priority under the Land Registration Ordinance (Cap.128 of the Laws of Hong Kong). For more information on the registration of tenancy documents, please go to the relevant question and answer.

The landlord of a domestic property should also submit a Notice of New Letting or Renewal Agreement (Form CR109) to the Commissioner of Rating and Valuation for endorsement within 1 month of the execution of the tenancy document. A landlord is not entitled to maintain a legal action to recover rent under a tenancy document (in case the tenant fails to pay rent) if the Commissioner does not endorse the Form CR109. However, a landlord who does not submit the form within the one month period may later do so after paying a fee of $310.

Episode 2: Applicability and Commencement of Regulated Tenancies

Episode 2: Applicability and Commencement of Regulated Tenancies

In this episode, we will look at which tenancies will be included in "regulated tenancies" and when regulation will start under the amended Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance.

We will explain the difference between a fixed-term tenancy and a periodic tenancy, and clarify when a fixed-term tenancy and a periodic tenancy will start to be protected by tenancy control. Additionally, we will discuss tenancies of subdivided units in industrial or commercial buildings and how to determine whether they qualify as "regulated tenancies".

The video will also cover how to determine whether a tenancy is a "regulated tenancy" through the Lands Tribunal or the Rating and Valuation Department.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

Rent

III. Rent

Episode 3: What is a "Standard Tenancy Agreement"?

Episode 3: What is a "Standard Tenancy Agreement"?

In this episode, we will explore the concept and details of the prescribed tenancy agreement for subdivided units.

We will explain the difference between oral and written tenancy agreements, and emphasize the importance of following the standard tenancy agreement. We will also discuss the potential conflicts between the tenancy agreement and the ordinance relating to the tenancy control of subdivided units, as well as the consequences that may arise from such conflicts.

Furthermore, we will discuss how to avoid conflicts between the tenancy agreement and the ordinance, and suggest that landlords proactively sign written tenancy agreements with tenants. We will explain how to download the standard tenancy agreement as a reference from the Rating and Valuation Department's website.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

Rates, Management Fees and other charges

IV. Rates, Management Fees and other charges

A better drafted lease/tenancy agreement shall also deal with the issues as to whether the tenant shall be responsible for payment of management fees, rates, government rent or other charges (such as utilities and telecommunication services).

In the absence of any express provision in dealing with such matters, it may generally mean that the ‘rent’ payable by a tenant covers all existing or ongoing expenses of the unit to be borne by the landlord and the tenant may not be liable to pay anything further.

Therefore, if the landlord so wishes, it would be a better practice to expressly set out under a lease/tenancy agreement as to the following areas:-

- Who shall be responsible for payment of rates, government rent, management fees and/or other charges;

- Whether the tenant shall open and/or maintain an account with the utility/service company themselves for the unit (e.g. water supplies department, drainage services department, sewage scavenger services (applicable to village houses), electricity, telephone, towngas, internet services andTV subscription) until the termination of the lease;

- Who shall be responsible for payment of any deposits and their return upon termination of the lease/tenancy agreement;

- When such payment shall be effected (i.e. pre-payment or when the fall due) and how tenant shall be given notice about the amount due;

- How such payment shall be made (i.e. directly to the payee (i.e. the Government, Management Office or utility company) and whether such payment obligation shall form (or be separated from) part of the rent;

- The consequences for non-payment of such fees/charges.

If existing utility account(s) are maintained by the landlord in respect of the unit, the landlord should make arrangements as to whether such accounts shall be transferred or replaced by another account under the tenant’s name. The tenancy agreement should also state as to upon termination of the lease (1) how outstanding amount(s) due should be paid, such as deduction from the rental deposit; and (2) if the tenant has paid any ‘deposit’ to such accounts maintained by the landlord, when and how such deposit shall be returned.

Landlords should note that, as the registered owner of the property, he/she remains to be primarily liable to the Government for any default on payment of government rent/rates.

The same also applies to management fees or other forms of contributions (e.g. renovation costs and contribution to litigation funds) to be made pursuant to the Deed of Mutual Covenant (“DMC”) or the Building Management Ordinance (Cap. 344) (the “BMO”).

Notwithstanding that a lease/tenancy agreement may provide that a tenant shall be liable to effect payment of management fees directly to the management office, such payment obligation is only privy between the landlord and tenant and is not binding on the manager or other co-owners. Moreover, since an obligation to pay money under the DMC/BMO is ‘positive’ in nature, by the effect of section 41(5) and (6) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance (Cap. 219), it is prima facie not directly enforceable by the manager/incorporated owners against a tenant so that the landlord remains to be liable for any tenant’s default on payments.

Episode 4: What is a "Cycle of Tenancy"?

Episode 4: What is a "Cycle of Tenancy"?

In this episode, we will explore the procedures and requirements during the regulated cycle of tenancy under the ordinance relating to the tenancy control of subdivided units.

We will provide a detailed explanation of the transition from the first term tenancy to the second term tenancy, as well as the procedures and considerations that need to be addressed during the regulated cycle. Additionally, we will discuss the renewal arrangements after the regulated cycle ends, as well as the legal regulations that landlords and tenants need to adhere to throughout the entire regulated cycle.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

How to recover the outstanding rent and get back the property?

V. How to recover the outstanding rent and get back the property?

A tenancy agreement may contain a clause that entitles the landlord to forfeit the tenancy (i.e. to terminate the tenancy and to re-enter the property) if the tenant fails to duly pay rent.

Even if the tenancy document does not contain a forfeiture clause, the law generally implies such a right of forfeiture upon non-payment of rent.

Regarding tenancies of domestic properties that were created on or after 27 December 2002, section 117(3) of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance implies in such tenancies a covenant on the part of the tenant to pay the rent on the due date and a condition for forfeiture if that covenant is broken by virtue of non-payment of rent within 15 days of the due date.

Regarding tenancies of non-domestic properties, section 126 of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance provides that in the absence of any express covenant for the payment of rent and condition for forfeiture, there will be implied in every tenancy a covenant to pay the rent on the due date and a condition for forfeiture for non-payment within 15 days of that date.

Therefore, in general, if a tenant is late in paying the rent for 15 days, the landlord is entitled to terminate the tenancy and obtain an order for possession from the Court (including the Lands Tribunal) to recover vacant possession of the property.

However, if the non-payment takes place for the first time during the course of a tenancy, the tenant who wishes to “save” the tenancy has a right to do so by paying all of the outstanding rent and the landlord’s legal costs in arrears at a specified time granted by the Court before the landlord could take possession of the property by the Court order. This is commonly known as “relief against forfeiture”.

Episode 5: Utility Bills and Miscellaneous Charges

Episode 5: Utility Bills and Miscellaneous Charges

In this episode, we will explore the relevant provisions of the ordinance relating to the tenancy control of subdivided units regarding the charges for water, electricity, gas, and communication services that landlords can impose on tenants.

We will explain the scope of charges that landlords can collect and provide important considerations regarding the apportionment methods. In addition, we will discuss the potential criminal offence of overcharging.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

Regulations on using or occupying a leased property

VI. Regulations on using or occupying a leased property

At first sight, a landlord should not have to bother with what the tenant is doing in the property as long as the tenant duly pays the rent and keeps the property in good condition. However, the issue is not as simple as that. A property used for a non-authorised purpose may create trouble for its owner.

Episode 6: Rights and Responsibilities

Episode 6: Rights and Responsibilities

In this episode, we will discuss the respective rights and responsibilities of landlords and tenants of subdivided units during the tenancy period.

We will explain the maintenance and repair obligations that landlords should fulfill, as well as the terms that tenants should abide by. In addition, we will also explore the consequences of landlords unlawfully depriving tenants of occupation as well as the protection of tenancy rights that tenants should enjoy if they abide by the terms.

To learn more about the regulation of subdivided units, please browse the content of "Sub-divided Flats and Tenancy Regulation".

Sub-letting

VII. Sub-letting

The Nature of sub-letting and its constraints

‘Sub-letting’ (also known as ‘under-letting’) of a property generally means that a tenant further lets out the property (or part of it) to another ‘tenant’ (known as ‘sub-tenant’) by another lease/tenancy agreement (known as the ‘sub-lease’ or ‘underlease’).

At law, a sub-lease executed between a tenant and sub-tenant is a separate and independent contract from the lease with the landlord (i.e. ‘head-lease’). However, notwithstanding that a tenant and a sub-tenant are generally at liberty to negotiate and agree upon the terms of a sub-lease to be different from the ‘head-lease’ (e.g. additional restrictive covenants to be imposed), the demised area and the term of a sub-lease are confined by the head lease. This is because the tenant has no right/interest to grant any interest in a sub-lease beyond the interest that he had been granted under the head-lease. For example:-

“A owns Flat A and Flat B. A lets Flat A to B for a term of 1 year. However, B entered into a ‘sub-lease’ of Flat A and Flat B to C for a term of 2 years.”

In such scenario, B may be regarded to be in breach of the terms of the ‘sub-lease’ because he had no interest be ‘let’ to C in respect of Flat B and any flat beyond a 1 year period.

Relationship between the tenant and sub-tenant

As between the tenant and the sub-tenant, a tenant may incorporate and enforce the terms and covenants of the ‘head-lease’ by incorporating a covenant under a sub-lease that the sub-tenant shall observe certain covenants under the head-lease. It is generally better practice for the tenant to expressly and specifically set out which covenants are to be complied with and provide a copy of the head-lease to the sub-tenant whenever possible (rather than incorporation by general reference to the ‘covenants of the head-lease’). However, since the landlord is not a party to the sub-lease, such covenant may only be binding and contractually enforceable by a tenant against a sub-tenant.

Effect of termination of head lease on the sub-lease

At law, the right of the tenant to grant a valid estate to a sub-tenant originates from the head lease. This means that, if the head-lease becomes ineffective (e.g. resumption/re-entry by the Government against the landlord or a third party being able to establish that he is the true owner of the land instead of the landlord) or terminated by the landlord for whatever reasons (i.e. non-payment of rent, other kinds of breaches committed by the tenant), the leasehold estate under the sub-lease will also become destroyed. In such case, notwithstanding that the sub-tenant might not be involved in any breach under the sub-lease, the sub-tenant will have no legal right or interest to possess and occupy the property vis-à-vis the landlord (or the Government/third party) and must deliver back the property.

The only possible relief of the sub-tenant is to apply for ‘relief against forfeiture’ from the Court of First Instance under section 58(4) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance (Cap. 219) for a ‘vesting order’ to vest the remaining term (or any less term) of the head-lease to the sub-tenant with conditions that may be imposed by the Court (e.g. to comply with any outstanding breaches committed by the tenant). If such discretionary relief against forfeiture is granted, the sub-tenant may be able to ‘stand into the shoes of the tenant’ and continue to occupy the property as if he was the tenant until the expiry of the ‘vested term’.

The inter-relationship between a landlord/tenant/sub-tenant may involve difficult legal concepts and tactical considerations. It is strongly recommended that legal advice should be sought from legal professionals in any of the aforesaid related matters.

Prohibition of sub-letting: If I have found that my tenant has sub-let my property to some other person without my consent, then what can I do to protect my interests?

To prohibit a tenant from sub-letting, it is necessary for a tenancy document to provide for an express clause that prohibits the tenant from subletting the property (or any part of it) to another party. It is also common practice of landlords to extend the prohibition against any act of licensing or sharing/parting of possession or occupation of the property.

If the tenancy document does not contain a clause that restrains a tenant from subletting, then the mere act of subletting of the unit (or part of it) to another person, even without the landlord’s consent, may not be illegal per se (subject to whether the tenant’s sub-letting has contravened any government regulations as explained above). As a tenancy has the effect of passing the landlord’s interests in the property to the tenant during the tenancy period, the tenant may deal with the property in whatever manner as if he owns the property (except for any illegal activities or actions which would amount to a breach of the tenancy agreement), including subletting the property to another party.

Based on the same reasoning, the breach of a prohibition clause on subletting may make the tenant liable to the landlord for injunction and/or damages. In certain cases, it may also enable the landlord to forfeit the tenancy agreement upon such breach.

In practice, even if a covenant against sub-letting is in force and without any other kinds of restriction, a tenant is still at liberty to cohabit, share occupation or use the property with other parties (who are often claimed to be guests, relatives or friends of the tenant). Prima facie, they do not fall within the ambit of ‘sub-letting’.

In the absence of any direct evidence that the tenant is engaging in sub-letting activities of the premises (e.g. copies of signed sub-leases, further partitions being made, admissions made by occupants, advertisements/ invitations made by tenant and excessive consumption of utilities), it is often difficult in practice for the landlord to prove and enforce restrictive covenants against sub-letting.

Properties with mortgages

VIII. Properties with mortgages

If the property has been mortgaged to a bank/financial institution, the landlord must obtain the consent of the bank/financial institution before leasing the property. Otherwise, it will have a negative impact on both the landlord and the tenant.

Repair/maintenance obligations

IX. Repair/maintenance obligations

Whether or not a party to the tenancy agreement is legally obliged to improve, maintain or carry out any repairs to a property is a complicated topic.

As an overview, the obligation to repair/maintain the subject property is mainly a matter of private contract between the landlord and the tenant. This means, in the absence of any express agreement between the parties with the obligation to repair/maintenance, there is generally no implied duty under a tenancy agreement to compel either the landlord or the tenant to carry out repairs or maintain the property in a fit and habitable state. The implied obligation on the landlord to maintain the property to be “fit for habitation” only applies to furnished lettings (e.g. serviced apartments or other leases with extensive furniture or fittings (e.g. sofa, bed, cupboards/cabinets/wardrobes, dining tables, curtains and/or electrical appliances) to be provided to the tenant in that the unit was ready for residential purposes without the need of purchasing any further essential fittings).

Very often, tenancy agreements do expressly provide for the landlord’s right to enter, inspect and/or carry out repairs to the property. But such right cannot be construed as a duty to be imposed on the landlord. Rather, it is common for tenancy agreements to stipulate that tenants are to be responsible to maintain/repair the internal and non-structural matters of the property and/or deliver back the property at its original handover state to the landlord (with fair wear and tear excepted) when tenancies are terminated.

There is an implied obligation on the part of a tenant to use the property in a tenant-like manner (i.e. to use the property in a reasonable and proper manner) and not to commit waste (i.e. not to destroy/damage the property). However, such duties only relates to the reasonable use of the property and does not impose any duty on the part of a tenant to carry out repairs.

Having said the above, the landlord may be under other statutory obligations to maintain the property as required by Government departments:-

- The Buildings Ordinance (Cap. 123 of the Laws of Hong Kong) confers power on the Building Authority to declare a building dangerous and to compel an owner to remedy any structural defects. However, this does not provide much assistance in the case of defects which are non-structural in nature.

- The Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance (Cap. 132) of the Laws of Hong Kong) confers power on specified public officers to require the owner or occupier of a property to cleanse the property or take steps to deal with nuisances which are injurious to health (e.g. water seepage which originates from the property itself). However, this only concerns the hygienic condition of the property and does not provide much assistance in terms of general repairs and maintenance, especially if any damage caused to the property was originated from by neighbours and/or the common parts of the building.

In respect of demands or orders issued by government authorities, it is almost invariable that the landlord, as the registered owner of the property, will be responsible for carrying out repairs or maintenance and any failure to comply with demands or orders often attracts penalties or other adverse consequences (e.g. re-entry by the Government). A tenant who receives such an order should duly inform the landlord so that the necessary steps can be taken as soon as possible.

Similarly, the Incorporated Owners of a building (or its management company) may also demand the landlord (or its occupants) to carry out appropriate steps to terminate any nuisance or other damage (e.g. dangerous structures, water seepage, drainage blockage and infestation of pests) caused to other occupants of the building.

For the reasons above and to avoid unnecessary disputes, it is most suitable for parties to enter into tenancy agreement which clearly specifies the obligations for repair and maintenance.

Termination of tenancies by notice before expiration (without breach)

X. Termination of tenancies by notice before expiration (without breach)

In usual circumstances, both the landlord and the tenant cannot terminate the tenancy before its expiration unless either of them has breached the vital terms of the agreement which entitles the other party to forfeit or terminate the tenancy (e.g. the tenant fails to pay rent or the landlord illegally re-enters the property).

However, early termination may be possible with the existence of a valid break clause which may be exercisable by either party by giving prior notice at a certain time during the term of the tenancy.

Landlord's perspective: 1, 5

Tenant's perspective: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Landlord sells the property with existing tenancy

XI. Landlord sells the property with existing tenancy

When a landlord intends to sell a property that is let to a tenant, the landlord should make it clear to the estate agent, the solicitors and the potential purchaser that the property will be sold subject to a tenancy (instead of delivering up “vacant possession”).

The landlord shall also state clearly in the sale and purchase agreement (or preliminary agreement) about the apportionment of rent (including unpaid rent as receivable from the tenant) before completion of the sale. The landlord should also notify the tenant about the intended sale and properly, the identity/contact method of the purchaser and the payment method (e.g. bank account of the purchaser) and deal with the deposit paid by the tenant.

To get more information about sale and purchase of property, please click here.

Renewal matters

XII. Renewal matters

Supposing that an existing tenancy is about to expire, the landlord and the tenant can commence negotiation on whether to renew the tenancy.

For tenancy agreements entered before 9th July 2004, a landlord was in most cases bound to renew a tenancy for a domestic property with an existing tenant under the law. However, the law has changed. Tenancy agreements entered after such date no longer offers any statutory right of renewal in favor of a tenant. A tenant could only ‘renew’ his tenancy either through negotiation or contractually exercising an ‘option to renew’ under a tenancy agreement (if so provided).

An ‘option to renew’ clause in the contract usually requires the tenant to give a written notice to the landlord not later than a date specified in the contract. The clause may also contain reference to the terms of the new tenancy document, such as on the same terms as the existing tenancy or a slight increase in payable rent over the renewed term of tenancy.

Subject to the agreement between the parties, an "option to renew" clause may look like this (for reference only):

“It is hereby agreed that if the Tenant wishes to take a further term of two years from the expiration of the Term and at least six months prior to such expiration gives the Landlord written notice to that effect and has paid the rent and all monies hereby reserved and reasonably performed and observed the terms and conditions on its part herein contained up to the expiration of the Term, then the Landlord will let the Property to the Tenant for a further term of two years from such expiration at a new monthly rent and subject to the same terms and conditions as are herein contained except this clause for renewal.”

Termination of tenancies (by non-payment of rent)

XIII. Termination of tenancies (by non-payment of rent)

For a tenant who fails to pay rent fully or partially, sometimes the tenancy agreement may contain an express clause which entitles the landlord to terminate (or ‘forfeit’) the tenancy agreement upon any extent of non-payment or late payment of rent.

Under sections 117 and 126 of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance (Cap.7), it is implied by law that non-payment of rent for more than 15 days of the due date would give rise to a right for the landlord to forfeit/terminate the tenancy agreement.

Alternatively, a landlord may also accept repudiation and terminate a tenancy agreement upon persistent non-payment of rent of a tenant for many months or there is evidence to suggest that the tenant has absconded/abandoned the property for good.

Upon termination/forfeiture of the lease, the landlord may claim for an order for possession of the property in Court (or the Lands Tribunal). If the tenant does not oppose such claim, such order would usually be made.

However, a tenant whom defaulted in payment of rent for the first time may apply for a grace period and would usually be given a chance by the Court or the Lands Tribunal (i.e. once during the term of the tenancy agreement) to pay up for all outstanding rent and the landlord’s legal costs at the time of hearing of the application or within a specified period after the possession order is made. This is commonly known as ‘relief against forfeiture’ (for non-payment of rent) which is governed under section 21F of the High Court Ordinance(Cap.4).

If ‘relief against forfeiture’ is granted to the tenant and he does pay up the in full all outstanding rent and the landlord’s costs within the stipulated period as imposed by the Court, the term of the tenancy agreement will become ‘resurrected’ upon the tenant’s compliance and be treated as continuing under its original terms as if there was no default on rental payment before. In such event, the tenancy will become ‘revived’ notwithstanding that this might be against the landlord’s wishes.

It must be noted that ‘relief against forfeiture’ can only be granted as of right upon the application of the tenant for once the Court during the duration of the tenancy agreement. If there is a repeated instance of non-payment of rent, the Court would decline to grant any relief unless good reason is shown by the defaulting tenant.

Termination of tenancies (for breaches of the tenant other than non-payment of rent)

XIV. Termination of tenancies (for breaches of the tenant other than non-payment of rent)

In the event that the tenant pays rent on time but commits serious breach(s) of the tenancy agreement (e.g. subletting, conducting illegal activities, causing nuisance, installation of illegal structures or causing enforcement actions by the Incorporated Owners), the landlord may wish to terminate the tenancy and find another replacement tenant.

In such case, it would be necessary for the landlord to rely on any forfeiture/termination clause as expressly provided under the tenancy agreement to put an end to the tenancy and claim possession from the tenant. If the tenancy agreement is silent on such matter, the landlord (for residential premises only) may only rely on section 117(3)(d) to (h) of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance (Cap. 7) to exercise implied rights of forfeiture as a fallback. Note that the law does not imply such right to terminate the tenancy agreement for tenancy agreements other than residential tenancies.

The landlord who wishes to terminate the tenancy on such ground is also required to give prior written notice to the tenant by specifying the breach and require the tenant to remedy the breach (or compensation payable) before termination and/or claiming possession of the property against the tenant.

When the claim for possession is heard before the Court, the Court has a discretion in deciding whether or not to grant ‘relief against forfeiture’ in favor of a tenant under section 58 of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance(Cap. 219) (i.e. continuation of the tenancy by the tenant who already ceased the breach and upon payment of all legal costs incurred by the landlord) by considering the seriousness of the breach, whether the breach was ‘remediable’ and/or whether any permanent damage/stigma was attached to the property.

Table 1

Table 1

The following table summarises the wording that may be used for the execution clause in a Lease/Tenancy Agreement.

Capacity of parties

Wording commonly used for the execution clause

Lease

Tenancy agreement

Signed, sealed and delivered by [name of party]

Signed by [name of party]

Sole proprietorship

Signed, sealed and delivered by [name of the sole proprietor] trading as [trading name of the sole proprietorship]

CHOPPED WITH the chop of the [Landlord/Tenant] and signed by [name of the sole proprietor] trading as [trading name of the sole proprietorship]

Partnership

Signed, sealed and delivered by [names of all partners of the partnership] trading as [trading name of the partnership]

CHOPPED WITH the chop of the [Landlord/Tenant] and signed by [names of all the partners] trading as [trading name of the partnership]

Limited company

Sealed with the common seal of [name of the company] and signed by [name(s) of the signatory(ies)], duly authorised by its Board of Directors

Signed for and on behalf of the [Landlord/Tenant, with company chop] by [name of signatory], duly authorised by its Board of Directors

Forfeiture of rental deposit and other consequences following termination by the tenant's breach

XV. Forfeiture of rental deposit and other consequences following termination by the tenant’s breach

It is common practice in Hong Kong for tenancy agreements to include payment of a ‘rental deposit’ in the amount equivalent to two months’ rent (or more in commercial premises) as security and as an ‘earnest of performance’ of obligations under the tenancy agreement.

However, it is often the case that most pro-forma agreements used might not contain an express provision for a right to forfeit the deposit as a consequence of breach. Very often, it is even more unclear as to the following matters which frequently arose in disputes between landlords and tenants regarding the treatment of the deposit:-

- Whether the deposit could be ‘used’ or ‘deducted’ by the landlord to satisfy the actual losses suffered as a result of tenant’s breach (e.g. unpaid management fees);

- Whether the deposit could be forfeited by the landlord absolutely and/or in full regardless of the degree and extent of the tenant’s breach (e.g. partial non-payment of rent for one month only);

- Whether the landlord must ‘give credit’ to the amount of deposit as forfeited in claiming damages against the tenant for losses sustained as a result of the breach;

- Whether the deposit shall be construed as ‘liquidated damages’ and/or whether landlord is entitled to recover any extra losses against which was suffered on top of to the deposit forfeited (e.g. repair costs);

- In the event that the tenancy continues, whether the tenant was obliged to replenish, top-up and pay to the landlord the amount of deposit as forfeited;

- When disputes arise after termination of the lease, whether the landlord is entitled to withhold return of the deposit until final resolution of Court proceedings.

The resolution of the above issues is case-specific which highly depends on the proper construction of tenancy agreements. There is no standard answers to the above matters. To avoid any unnecessary dispute between parties, it is recommended that the tenancy agreement do expressly address the above matters in relation to treatment of the rental deposit.

More importantly, it is a common misconception on the part of tenants that, after termination of the tenancy agreement upon breach of the tenant (i.e. non-payment of rent which resulted in ejection), the compensation payable to the landlord shall be confined to the amount of the deposit and there shall be a ‘clean break’ between the parties after termination. This is wrong because a landlord might have sustained further losses (e.g. loss of rent due to the inability to find a replacement tenant for the remainder of the unexpired term of the lease) as a result of the tenant’s wrongful termination (i.e. repudiation).

In such event, assuming the landlord had taken reasonable steps to mitigate his losses, even the tenant did NOT occupy the property after termination, he may become prima facie liable to compensate the landlord the outstanding rent for remainder term as ‘consequential losses’. This may end up in a very harsh result for the tenant in the event that the unexpired term is a long one (See: Goldon Investment Ltd v. NPH International Holdings Ltd HCA 5457/1999 (10th August 2004) A tenant was held liable to pay to the landlord an amount of HKD 17 million as a result of non-payment of 2 months rent).

For such reason, wrongful termination of the tenancy agreement on the part of the tenant is a very serious matter which must not be taken lightly.

Handover matters at expiry/termination of a lease

XVI. Handover matters at expiry/termination of a lease

It is another common problem in Hong Kong that tenancy agreements do not explicitly provide for the conditions of the property to be handed over back to the landlord at the time of termination or expiry of the tenancy agreement. This often constitutes a source of litigation between parties as to whether and to what extent a tenant shall be obliged to incur costs in restoring the property back to the ‘original’ state.

Generally, a tenant is under no obligation to ‘improve’ the property into a better state than what was given to him at the commencement of the tenancy. It is also expected that the property may suffer from fair wear and tear as result of aging and normal use in which the landlord may have to reasonably accept at the time of handover.

It is common for tenancy agreements to list out the ‘landlord’s fixtures’ that the tenant shall be ‘handed back’ to the landlord at handover of the property at a reasonable status or replacements at equivalent value after depreciation (e.g. air-conditioners, electrical/cooking/heating appliances, bathing and sanitary fittings, built-in closets, doors and windows etc.).

For renovations carried out by the tenant within the property, it is a more complicated matter as to whether the landlord would be willing to accept delivery up of the property with such state given that renovations are often a matter of personal preference.

For commercial premises, it is often common for tenancy agreements to include an express obligation to delivery up of premises at a ‘bare-shell’ state to the reasonable satisfaction of the landlord (i.e. removal of all fixtures, including electrical/drainage appliances, ceilings, ground layers, sanitary fittings and fire-service installations, and leaving behind only the plastering/concrete surfaces).

There is no definitive indicator as to what constitutes ‘reasonable satisfaction of the landlord’ (which denotes a rather subjective and arbitrary standard). The duty to deliver up a ‘bare-shell’ is often an onerous and costly obligation for tenants to comply with. A tenant must quit earlier to allow sufficient time for restoration works to take place.

In practice, to avoid unnecessary disputes, it is often desirable for both parties to sign on a written acknowledgement about the state of handover of the property after inspection.

1. Is it necessary to have a solicitor to represent me when I enter into a Tenancy Agreement?

1. Is it necessary to have a solicitor to represent me when I enter into a Tenancy Agreement?

No law requires a party to a contract to be represented by a solicitor. As a matter of fact, some people enter into standard form tenancy agreements without obtaining legal advice or even without reading the contents of the agreements.

Depending on the circumstances, some parties may also enter into leases/tenancy agreements with the assistance of estate agents in recording the agreed terms under a standard form provided and including whatever additional clauses that they wish to add.

A template residential tenancy agreement which was drafted by a team of law lecturers and students of the University of Hong Kong is now available on CLIC. Please refer to “E-package: DIY Residential Tenancy Agreement” for reference.

Parties that have the benefit of solicitors, however, have their legal interests better protected because their solicitors will draft or scrutinise a written tenancy agreement from a legal perspective with the parties’ interests in mind.

A tenancy document prepared by solicitors typically covers more aspects than standard form agreements because the former tends to identify more issues that can potentially lead to disputes. By identifying and dealing with these issues before the parties commit themselves to the terms of the tenancy, the chance of future disputes between the parties may be reduced.

It is more common for parties in commercial or industrial tenancies to be legally represented by solicitors to cater for their specific needs and interests. This is particularly the case when both parties are body corporates (e.g. companies) and that there might be a need for the landlord to require a natural person to act as guarantor on behalf of the tenant to ensure due performance of all obligations under the tenancy agreement.

Last revision date:

28 February, 2020

2. I heard about someone who claimed that they were the owner of a property for let. After the potential tenant had paid the deposit and the rent in advance, the “landlord” disappeared with the money. If I am going to rent a property, then how can I be sure that the landlord is the real owner?

2. I heard about someone who claimed that they were the owner of a property for let. After the potential tenant had paid the deposit and the rent in advance, the “landlord” disappeared with the money. If I am going to rent a property, then how can I be sure that the landlord is the real owner?

The Land Registry provides a “Land Search” service to the public. Any person can conduct a search at the Land Registry to ascertain the ownership particulars of any property in Hong Kong. A potential tenant should always conduct a land search before entering into a tenancy document to verify the identity of the landlord (or his/her representatives).

If the potential tenant is renting the property through an estate agent or has retained a solicitor firm, then the agent and the firm are duty bound to conduct such a search to protect the tenant's interests.

To best safeguard one’s interests, it is also appropriate for the prospective tenant to request the landlord to actually enter and view the unit to be let in the presence of estate agents before entering into any tenancy agreements.

Last revision date:

28 February, 2020

1. How is stamp duty calculated on a tenancy document?

1. How is stamp duty calculated on a tenancy document?

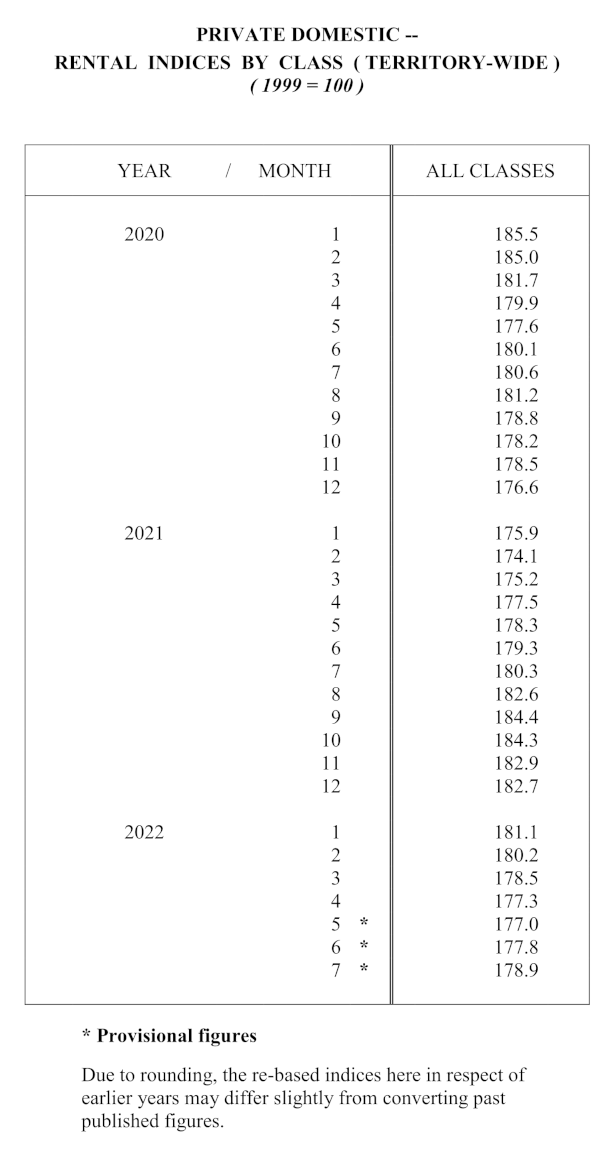

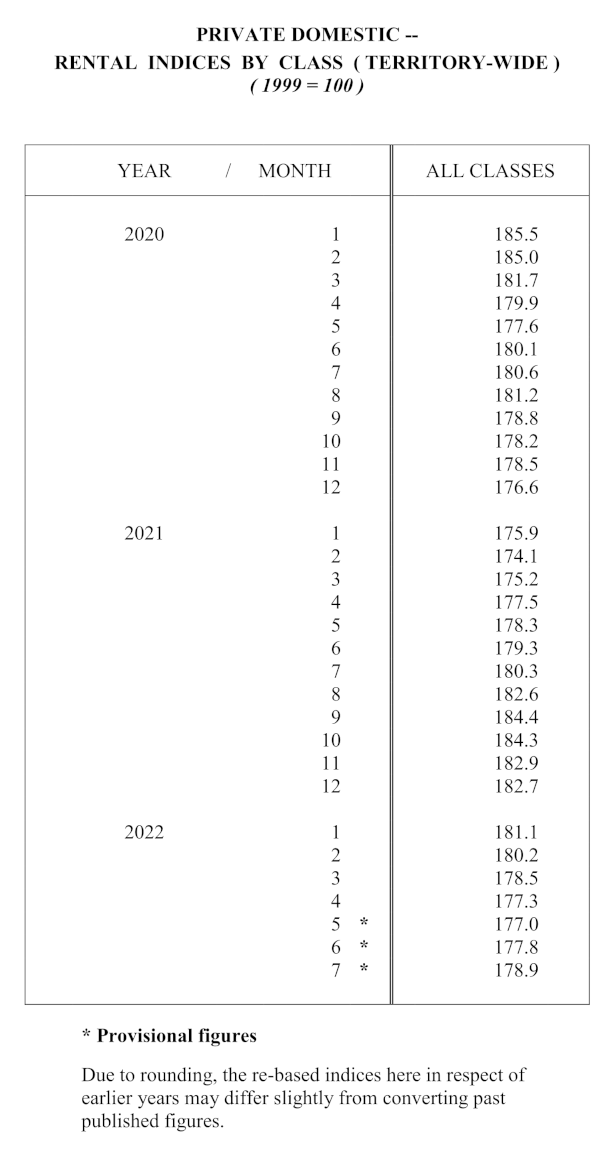

Stamp duty is a tax on certain written documents that evidence transactions. Parties to a tenancy document are liable to pay stamp duty on the document according to Schedule 1 of the Stamp Duty Ordinance (Cap. 117 of the Laws of Hong Kong). The rate of stamp duty varies with the term/period of the tenancy. The current rates are as follows.

Term of the tenancy

Rate of stamp duty

Not defined or uncertain

0.25% of the yearly or average yearly rent

Not exceeding 1 year

0.25% of the total rent payable

Exceeding 1 year but not exceeding 3 years

0.5% of the yearly or average yearly rent

Exceeding 3 years

1% of the yearly or average yearly rent

$5 is also be payable for the stamping of each counterpart of the tenancy document.

A licence does not transfer any interest in land and is not liable for stamp duty. However, if there is any doubt as to whether a tenancy document is liable for stamp duty, then it is good practice to seek adjudication from the Stamp Office. The current adjudication fee is $50.

No law specifies whether the landlord or the tenant should pay the stamp duty. Therefore, the parties to a Tenancy Agreement can freely agree between themselves on their respective shares of stamp duty. In most cases, the parties will pay the stamp duty in equal shares.

Example

There is a two month rent-free period in a tenancy with a term of three years and a rent of $10,000 per month. How can the stamp duty be calculated for this Tenancy Agreement?

The stamp duty chargeable on a tenancy document and its counterpart is based on the rent payable or the yearly or average yearly rent. A rent-free period will therefore diminish the base on which stamp duty is calculated. The following examples will serve to illustrate how a rent-free period affects the stamp duty payable.

A property is let for $10,000 per month and the term of the tenancy is 3 years without a rent-free period. The stamp duty payable is:

($10,000.00 x 36)/3 x 0.5% + $5 = $605

A property is let for $10,000 per month and the term of the tenancy is 3 years with a rent-free period of 2 months. The stamp duty payable is:

($10,000 x (36 – 2))/3 x 0.5% + $5 = $572

2. What are the consequences of failing to stamp a tenancy document?

2. What are the consequences of failing to stamp a tenancy document?

An obvious consequence is that the landlord and the tenant will be liable to civil proceedings by the Collector of Stamp Duty of the Inland Revenue Department. Moreover, a tenancy document must be stamped before it can be lodged with the Land Registry for registration.

A more important consequence is that the Court may not accept an unstamped tenancy document as evidence in civil proceedings. In other words, a party will have difficulties in enforcing the tenancy document against the other party (who has breached the Tenancy Agreement or Lease) in Court.

3. Some tenancy documents must be registered with the Land Registry but some do not. Why?

3. Some tenancy documents must be registered with the Land Registry but some do not. Why?

The major purpose of registering documents at the Land Registry is to notify the public of all documents affecting lands in Hong Kong and to set up a priority system regarding documents affecting a particular property. Once a document is registered, the public is deemed to have notice of its existence and its content. The date of registration also affects the priority of a party’s rights in a particular property. A written tenancy agreement, being an instrument affecting land, is of course registrable at the Land Registry.

The laws that govern the registration of documents at the Land Registry are contained primarily in the Land Registration Ordinance ( of the Laws of Hong Kong). Strictly speaking, the Land Registration Ordinance does not contain any provision that compels the registration of documents. It only spells out the consequences of non-registration. Therefore, the question should be: why is it that some tenancy documents should be registered with the Land Registry?

Lease and Tenancy Agreement

Although a tenancy document is registrable with the Land Registry, Section 3(2) of the Land Registration Ordinance provides that the principles of notice and priority do not apply to "bona fide leases at rack rent for any term not exceeding 3 years". Therefore, a document that creates a tenancy for a term of more than 3 years (i.e. a Lease) should be registered, otherwise it is prone to be defeated by successors in title of the landlord (e.g. purchasers or new tenants) and will lose its priority against other registered documents that affect the same property. In such event, the existing tenant may become evicted.

In contrast, a document that creates a tenancy for a term of 3 years or less (i.e. a Tenancy Agreement) does not gain or lose anything by registration.

However, if a Tenancy Agreement contains an option to renew the existing tenancy, it should be registered even though the term of the tenancy does not exceed 3 years. An option to renew confers on the tenant a right to continue to rent the property after the expiry of the current term, i.e. to renew the existing tenancy. As this exercisable option to renew represents a legal interest in land and affects the principles of notice and competing priority with third parties, the relevant Tenancy Agreement should be registered.

To play safe, parties to a Tenancy Agreement should check with legal professionals to ascertain the necessity of registration.

4. How is Property Tax calculated?

4. How is Property Tax calculated?

Property Tax is computed at the standard rate of 15% (from 2008/2009 assessment year onwards) on the “net assessable value” of the property. A “Net Assessable Value” is computed as follows:-

| [A] | Rental Income |

|---|

| [B] | Less: Irrecoverable Rent |

|---|

| [C] | (A-B) |

|---|

| [D] | Less: Rates paid by owner(s) |

|---|

| [E] | (C-D) |

|---|

| [F] | Less: Statutory allowance for repairs and outgoings (E x 20%) |

|---|

Net Assessable Value: [E]-[F]

It is notable that “Rental Income” covers the following:-

- Gross rent received

- Payment for the right to use premises under licence

- Services charges or management fees paid to the owner

- Landlord’s expenditure borne by the tenant, e.g. repairs and property tax paid by the tenant

- Lump sum premium

As explained, the law imposes a flat rate of 20% as statutory allowance for repairs regardless of the actual amount(s) being spent or incurred in repairing/refurbishment of a property by the landlord.

Further deductions may be made through election on “Personal Assessment” (for properties wholly owned by individuals)

Based on the foregoing, it is commonplace for tenants to become responsible for and pay management fees directly under a tenancy agreement, while it is usually the landlord who shall be responsible for payment of government rent/rates by themselves.

For details regarding the exact computation of Property Tax, please visit the Inland Revenue Department’s website.

1. My tenant has failed to pay rent for two months. What can I do to recover the rent and the possession of my property?

1. My tenant has failed to pay rent for two months. What can I do to recover the rent and the possession of my property?

If a tenant fails to pay rent, then the following measures are usually available to the landlord.

a) Action for the recovery of outstanding rent

If landlords intend only to recover the outstanding rent but not to regain possession of the properties, then they may make their claim for rent arrears at one of the followings.

- The Small Claims Tribunal: for claims of $75,000 or less (To get more information about how to prepare for the trial (from both the Claimant's and the Defendant's perspective), please click here;

- The District Court: for claims that exceed $75,000 but do not exceed $3,000,000;

- The Court of First Instance of the High Court, which has unlimited jurisdiction.

Landlords of domestic properties domestic property, should ensure that they have submitted a Notice of New Letting or Renewal Agreement (Form CR109) to the Commissioner of Rating and Valuation for endorsement within one month of the execution of the tenancy document. Landlords of domestic properties are not entitled to maintain legal action to recover rent under tenancy documents if the Commissioner does not endorse the form. However, landlords who do not submit the form within the one month period can do so at any time after paying a fee of $310.

b) Action for forfeiture (to get back the property) and to recover outstanding rent

In the case of serious default on payment of rent or in the event that landlords believe that their tenants have been absconded or will not be able to pay the rent for the remaining term of the tenancy, then they will probably want to get back the property and recover the rent in arrears. In such circumstances, the landlords are said to be exercising their right of forfeiture and may file their claims at:

- the Lands Tribunal;

- the District Court if the outstanding rent does not exceed $3,000,000 and the rateable value of the property does not exceed $320,000; or

- the Court of First Instance of the High Court for outstanding rent of any amount.

The landlord, if successful in obtaining a judgment against the tenant, will be able to apply to the tribunal/appropriate court for a Writ of Possession. Upon the issue of the Writ of Possession, the court bailiff will recover the possession of the property on the landlord’s behalf.

Jurisdiction of the High Court

It should be noted that although the High Court has unlimited jurisdiction to handle any of the above claims, it normally will not entertain a claim that falls within the jurisdiction of the District Court or the Lands Tribunal.

Application for Summary Judgment for possession/Interim payment

After commencement of proceedings, it may take some time to wait for trial to take place at Court (especially for the District Court/Court of First Instance). However, for many cases, there may be procedure for landlords to recover possession/rent in a more speedy fashion known as “summary judgment” or “interim payment” if the landlord is satisfied that there is no arguable defence on the part of the tenant to resist an application for an order of repossession and/or payment of outstanding rent.

You must seek legal advice on any grounds for obtaining a summary judgment or an interim payment before you make the relevant application to court.

c) Action for distress

Distress means the seizure, detention and sale of movable chattels/goods found in the rented property to satisfy the rent arrears pursuant to a warrant issued by the District Court upon application by the landlord. Due to the nature of distress, it is mostly used in cases in which a tenant is still operating a business at the rented property. Part III of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance governs the procedures and formalities for applications for distress.

The application for distress is an ex-parte application (by one party only) to the District Court, meaning that the tenant will not have the chance to appear before the judge to make any submission (or objection). This is to avoid the tenant knowing of the application and dissipating the available assets.

The landlord must file an affidavit/affirmation to support the application in a prescribed form. If the Court accepts the landlord's application, then a warrant of distress is issued. The bailiff then enters the property, seizes the movable chattels/goods found inside and in the apparent possession of the tenant, and sells the chattels/goods to satisfy the rent in arrears.

Note that the bailiff cannot seize land fixtures (e.g. air-conditioning machines and, some built-in appliances), things in use, tools and implements or the goods which is apparently owned by parties other than the tenant. The goods as seized will be impounded by the bailiff until the rent is paid or being sold by an auctioneer as the Court may direct.

As distress is complicated both in terms of procedures and legality, it is usually done with the assistance of legal professionals.

2. My tenant has failed to pay rent for several months. Can I regain possession of my property by breaking open the door, throwing away the tenant's belongings and changing the lock without resorting to Court proceedings?

2. My tenant has failed to pay rent for several months. Can I regain possession of my property by breaking open the door, throwing away the tenant's belongings and changing the lock without resorting to Court proceedings?

It must be borne in mind that if the property is still being occupied by the tenant (or some other occupants), any forcible entry by the landlord into the Property without obtaining any court order may amount to criminal offence under section 23 of the Public Order Ordinance (Cap. 245).

The landlord may also face other criminal charges such as ‘harassment’. Section 119V of the Landlord and Tenant (Consolidation) Ordinance (Cap. 7) expressly provides that any person who unlawfully deprives a tenant of occupation of the relevant premises commits an offence and may be liable to a fine or even imprisonment.

A tenancy document will usually contain a clause that allows the landlord to re-enter the property if the tenant fails to pay rent. In the event that the landlord is sure that the tenant has deserted and abandoned the property in a vacant state (or only with inexpensive belongings left behind) for a reasonably long time, the law may recognize a right for the landlord treat the tenancy as terminated and quietly re-enter the premises by himself without resorting to court proceedings (i.e. self-help). For some owners in Hong Kong, this might be a convenient and inexpensive way to recover possession against absconding tenants.

However, it is generally unsafe for the landlord to rely solely on such method and re-enter the property by self-help. There is always a risk that the tenant may reappear a few months later and allege that the landlord has wrongfully re-entered into the property or that valuables left in the property became misappropriated.

Therefore, even if it may be quite certain that the tenant has deserted the property, the landlord should go through the appropriate legal procedures, which will eventually lead to the recovery of the property with the assistance of the bailiff.

3. My tenant has failed to pay or allegedly 'deducted' the rent for several months by the excuse that he suffered from minor water leakage problems or discomfort/disturbances. Can he/she do so and is that a good defence to the recovery of the payable rent/forfeiture?

3. My tenant has failed to pay or allegedly 'deducted' the rent for several months by the excuse that he suffered from minor water leakage problems or discomfort/disturbances. Can he/she do so and is that a good defence to the recovery of the payable rent/forfeiture?

Shortly speaking, the issue generally depends on whether the obligation to pay rent was dependent on the fulfillment of any obligations on the part of the landlord (e.g. repair or quiet enjoyment, if so agreed) and/or whether the tenancy agreement expressly allowed the tenant to 'deduct' any rent payable by any reason.

In most situations and in the absence of any special clauses under the tenancy agreement, the tenant's obligation to pay rent is independent of other obligations to be performed by the landlord. Simply put, no 'rent' is likely to become 'deductible' or 'set-off' as such even if the allegation of the tenant may appear to be true.

This is to say, the complaints by a tenant over the standard/quality/condition of living in the property is unlikely to constitute a sound legal defence to non-payment of rent. As explained, non-payment of rent alone would enable the landlord to exercise his/her right to claim for outstanding rent and even forfeit the tenancy (subject to relief against forfeiture exercisable by the tenant).

The above is only a preliminary analysis of general propositions of the law and whether such principle is applicable to all cases would be heavily dependent on the terms of the tenancy agreement and exact individual circumstances. If you encounter such subject matter, you are definitely recommended to seek assistance from legal professionals.

1. Why is it necessary and how do we ascertain the primary use, for example “domestic” or “non-domestic”, of a property?

1. Why is it necessary and how do we ascertain the primary use, for example “domestic” or “non-domestic”, of a property?

A tenancy document may contain a clause which specifies that the property is only to be used for domestic or non-domestic purposes (or in accordance with the uses permitted by law/regulations). If the tenant runs a shop in a residential property, the use may constitute a breach of such covenant.

To support any intended claim, the landlord may obtain evidence/proof of such a breach before proceeding with any further action (e.g. taking of photographs). Sometimes it may be difficult to obtain evidence from the management office (e.g. CCTV records) or ask caretakers/neighbours to give evidence in Court.

Where a question or dispute arises about whether a property is used for domestic or non-domestic purposes, one may also ask the Rating and Valuation Department to issue a Certificate of Primary User of Premises for verification. If the dispute has been brought up to the Court, then you should submit Form TR4 to apply for the Certificate. If the dispute has not yet been brought up to the Court, then you should submit Form TR4D and pay the application fee of $3,850. Although the Certificate does not provide a conclusive answer to the issue, it will be persuasive when the issue is brought to Court. For more details regarding the Certificate, please contact the Rating and Valuation Department at 21520111 or 21508229.

An owner may also check from the Government Lease (including any conditions of grant), the Occupation Permit (issued by the Buildings Department), the Approved Building Plans (by the Buildings Department) and/or the Outline Zoning Plan (from the Town Planning Board) to ascertain the permitted use(s) of the property as under the law. These documents, however, are technical in nature and might not be easy to read and properly understood without professional assistance.

For owners of multi-storey buildings, it may also be prudent to also check from the Deed of Mutual Covenant for any user restrictions in the unit (or even the common area of the building).

2. I have let a residential property to a tenant and I recently found that the tenant is using the property as an office. Will this affect my interests or cause any liability to me as a landlord? If my tenant conducts criminal activities there, what further problems will I face?

2. I have let a residential property to a tenant and I recently found that the tenant is using the property as an office. Will this affect my interests or cause any liability to me as a landlord? If my tenant conducts criminal activities there, what further problems will I face?

A property that is used for a unauthorized purpose may create trouble and/or legal liability for its owner (the landlord) in the following ways.

Breach of Government Lease

All lands in Hong Kong (except the piece on which St. John's Cathedral is standing) are owned by the government, and landowners only lease their land. A typical owner of a flat in a building is therefore only a ‘tenant’ (of the Government) and co-owner of the shares in the land on which the building stands. When the government leases a piece of land to the "owner", a contract is signed. The contract, generally called a Government Lease, imposes various conditions on the "owners" and their successor in title. One commonly found condition is that the "owners" have to comply with the land use purpose specified in the Government Lease. If there is a breach of this condition, for example conducting business activities at a property designated for residential use, then the government is entitled to re-enter and take back the possession of the property as its own.

Although such a drastic measure is seldom used, in serious cases the Lands Department has no hesitation in re-entering properties where its occupants continued its breaches in blatant disregard of warnings given. The Government is entitled to exercise its powers under the Government Rights (Re-entry and Vesting Remedies) Ordinance (Cap. 126) by registering a memorial of an instrument of re-entry in the Lands Registry and upon such registration, the property is deemed to have been re-entered by the Government so that the owner will cease to become an owner of such land with immediate effect. In such event, under section 8 of the said ordinance, the former owner may only petition to the Chief Executive for the grant of relief (if a breach is admitted to have been committed) or apply to the Court of First Instance if disputes arose.

Breach of the Deed of Mutual Covenant

A deed of mutual covenant is a contract that is binding on all owners of a multi-unit or multi-storey building. It basically sets out the rules for the management of the building.

A standard deed of mutual covenant will state that a unit owner must comply with the terms of the relevant Government Lease and will use the property only for the authorised purpose(s). A unit owner will usually also be required to prevent the tenant or occupiers from breaching the relevant terms. Therefore, even though it may be the tenant who is in breach of the Government Lease and the deed of mutual covenant, the landlord can still be liable to legal action by the management company, the incorporated owners (if any) or the other unit owners of the building.

Liability to a third party

If a residential property is used for business purposes, then one can naturally expect that more visitors than originally anticipated will frequently enter into the vicinity of the property. The risks of such visitors suffering from accidents related to the property and thus claiming against the landlord will also increase.

A well-drafted tenancy document may contain a clause which specifies that the tenant shall indemnify the landlord from and against all claims and liabilities caused by the tenant’s acts or omissions. However, if the landlord does not have a well-drafted tenancy document, there may be a vacuum in the terms of liability to be borne by the landlord or tenant. In such circumstances, the landlord may be entangled in totally unanticipated litigation caused by unauthorized uses or accidents which occurs within the property by its occupants.

Criminal liability

If the tenant is merely using the property for purpose(s) other than that authorised, then the worst that the landlord will face is monetary loss and damages. However, if the landlord knows that the tenant is using the property for criminal activities, e.g. as a gambling place or a vice establishment, and does nothing about it, the landlord may face criminal liability.

Any illegal use of the property is also likely to trigger the enforcement of the Government Lease (by the Lands Department) or the Deed of Mutual Covenant (by other co-owners) as explained above against the owner directly.

As a tenancy document is likely to contain a clause that designates the use of the property, e.g. residential, retail, or industrial. The tenant's breach of this clause may give rise to the landlord's right of forfeiture. The landlord may also want to seek professional legal advice about the landlord's rights and liabilities, including a possible application for the grant of an injunctive relief. For instance, a tenant who uses a residential property as a “home office” may simply be using it as a business correspondence address with all transactions made on a computer. While it may be argued that the use of the property might have included business elements, there may not be any actual harm to the property or any actual negative effects to the landlord. In such circumstances, even though the tenant may be technically in breach of the term of the tenancy document, an injunction (whether temporary or permanent) might not lie as of right in favor of the landlord.

3. I am a tenant of an apartment unit who have been disturbed by my neighbour (since he habitually sings karoake at a high volume at night). I complained to the manager of the building and was told that as I was not the owner of the property. He further stated that, as tenant, I did not have any right under the deed of mutual covenant. Is he correct and what can I do?

3. I am a tenant of an apartment unit who have been disturbed by my neighbour (since he habitually sings karoake at a high volume at night). I complained to the manager of the building and was told that as I was not the owner of the property. He further stated that, as tenant, I did not have any right under the deed of mutual covenant. Is he correct and what can I do?

A deed of mutual covenant is a contract binding on all owners of a multi-unit or multi-storey building. It basically sets out rules for the management and regulation of the building. A typical deed of mutual covenant will state that a unit owner shall not cause or permit nuisance either created by the owner or his/her tenant to other occupiers of the same building.

It is technically incorrect to say that a tenant does not have any right under the deed of mutual covenant. In fact, the law confers a right to a tenant to enjoy and enforce the benefit of all covenants relating to land under the deed of covenant against other co-owners and their tenants. As such, the tenant may have the right to sue his/her noisy neighbours directly to enforce the said covenants under the deed of mutual covenant in Courts (e.g. Lands Tribunal). by obtaining an injunction and/or compensation for any harm or damage caused.

The manager of the building is also mostly likely to be under a duty to enforce restrictions under the deed of mutual covenants against all owners and their tenants. If there is an incorporated owners of the building (i.e. an “IO”), the IO will also be under a statutory duty to enforce the provisions under the deed of mutual covenant. In the event that the manager/incorporated owners willfully refuses to take any step to remedy the situation, the tenant may consider commencing a claim to compel such parties to enforce their duties.

Likewise, a tenant is also under an obligation to comply with the negative/prohibitive covenants under the deed of mutual covenant (e.g. an owner shall not cause any nuisance or annoyance in his unit). Any breach of the same may be subject to claims to be made by co-owners, the manager of the building and/or the IO.

In the event the tenant finds himself/herself facing with a deed of mutual covenant which is silent on the issue of nuisance, another option is probably to sue the singing neighbour under the law of nuisance by obtaining an injunctive relief as well as monetary compensation for the disturbances caused.

As the relevant legal procedures are complicated both procedurally and evidentially, it is strongly recommended to obtain lawyer's assistance in such regard.

1. I received a letter from a bank claiming to be the mortgagee of the property that I am renting. The bank claimed that the tenancy document between my landlord and me was made without its consent and asked me to move out of the property. What can I do?

1. I received a letter from a bank claiming to be the mortgagee of the property that I am renting. The bank claimed that the tenancy document between my landlord and me was made without its consent and asked me to move out of the property. What can I do?

All properly drafted mortgages may contain a clause that requires the mortgagor (the landlord) to seek consent from the mortgagee (the bank) before the mortgagor lets the property to another party (the tenant).

If the landlord complies with this requirement, then the bank has notice of and consented to the tenant’s presence and may not evict the tenant even if the bank eventually exercises its power of repossession (or forfeiture) under the mortgage upon any default on repayment. The bank, under such circumstances, will become the landlord and is entitled to receive rent from the tenant.

If the landlord lets a mortgaged property to a tenant without obtaining the bank's consent, then the landlord is in breach of the mortgage and the property is liable to be repossessed by the bank. When the bank eventually exercises its power of repossession under the mortgage, the tenancy agreement may not be effective to protect the tenant’s interest against the right exercisable by the bank. In such event, the tenant may become a trespasser on the property and the bank is perfectly entitled to ask the tenant to leave even if the tenant is prepared to pay the rent.

As a mortgage will invariably be registered with the Land Registry, the tenant is deemed to have notice of the mortgage and its terms. If the bank exercises its power of repossession under the mortgage, then the tenant cannot use ignorance as an excuse. Therefore, before entering into a tenancy document, a tenant should always conduct a land search at the Land Registry to check whether the property is mortgaged. If the answer is affirmative, then the tenant must ensure that the landlord has obtained consent from the mortgagee.

1. In general, who shall be responsible for maintaining and repairing the property?

1. In general, who shall be responsible for maintaining and repairing the property?

As explained above, when dealing with the issue of repair and maintenance, the landlord and the tenant must predominantly rely on the tenancy document to ascertain their respective duties on a contractual basis.

A commonly adopted approach under tenancy agreements is that the landlord is responsible for external and structural repairs and maintenance, and the tenant is responsible for internal and non-structural ones. However, such a simple dichotomy may still be problematic because the words internal, external, structural and non-structural can have different interpretations under different circumstances.

Therefore, a well-drafted tenancy document will try to anticipate and accommodate all potential areas of dispute that are specific to the particular property, and clarify the parties' duties in details.

As a matter of common practice and depending on the parties’ bargaining abilities, it will also be quite normal for a tenant to become responsible for many onerous duties which includes the carrying out of repair and maintenance works to a certain extent. Such term may be unfair on its face but in reality, it is actually quite reasonable because the tenant has full rights of occupying and dealing with the property on an ongoing basis during the term of the tenancy. Naturally, a tenant would be in a position to ascertain defects and carry out repair works which are necessary.

It is also common to find in a tenancy document that the tenant's obligations for repair and maintenance are limited by the phrase "fair wear and tear excepted". This excuses the tenant from damage arising from the passing of time and the ordinary and reasonable use of the property. A well-drafted tenancy document should also contain a clause which specifies that the landlord's obligations for structural repairs and maintenance will arise only upon notice of the structural defects. This is reasonable because the landlord, not being in occupation of the properties, cannot be expected to remedy defects or problems of which they are not aware of or not having any control over.

On the whole, the answer to the question of who is responsible for repairs and maintenance is to be found in the terms agreed upon by the landlord and the tenant. If there is no written tenancy document or if the particular issue is not tackled by the tenancy document, then the outcome of any dispute may turn out to be highly uncertain and costly.

Irrespective of parties’ rights and obligations as agreed, the landlord may also volunteer to carry out repairs and maintenance works out of goodwill and preservation of relationship with tenant. Indeed, as most tenancy agreements in Hong Kong are short-termed, any state of disrepair or resultant damage caused by defects would most likely be detrimental to the landlord’s interests in the long run. On such basis, it is often the case that the landlords do agree to incur expenses to remedy any defects in the property (e.g. patching up of damaged walls, replacement of faulty air-conditioners/refrigerators andinjection of termite/insect repellents etc.).

In extreme cases (e.g. serious water leakage within the property), the landlord may also exercise a right (if so provided under the tenancy agreement) to enter the property and carry out necessary inspection and repair works by giving prior notice/appointment notwithstanding that the tenancy agreement did not impose any duty on him/her. If the tenant becomes uncooperative, the landlord may even apply for an urgent interlocutory injunction in Court to exercise such right or even terminate the tenancy agreement for such reason.

2. If there was a fire broken out on a leased property and the landlord has suffered some losses as a result, can the landlord claim against the tenant?

2. If there was a fire broken out on a leased property and the landlord has suffered some losses as a result, can the landlord claim against the tenant?

It depends on the terms agreed by the landlord and the tenant in the tenancy agreement. It also depends on the cause of the fire (e.g. the source of the fire, was it a pure accident or was it caused by someone's negligence or even willful damage). In practice, it is not easy to determine who was at fault.

A prudent landlord will take out insurance policies to cover the relevant property and household damage. Loss of or damage to household contents such as furniture, decoration, electrical appliances and personal valuables can be insured. A typical example of such kind of insurance is a "Householder's Comprehensive" insurance.

Another important note is that the landlord has a duty to inform the insurance company that the flat/house is rented out to a tenant.

Subject to the terms of the relevant tenancy document, the tenant may also be required to take out proper insurance for the property.

1. I have let my property to a tenant on a three year term. There are still more than 2 years remaining in the term. However, I note that the rental value of neighbouring properties has risen significantly. Can I terminate the tenancy with the existing tenant and re-let the property out for a better rent?

1. I have let my property to a tenant on a three year term. There are still more than 2 years remaining in the term. However, I note that the rental value of neighbouring properties has risen significantly. Can I terminate the tenancy with the existing tenant and re-let the property out for a better rent?